Fostering the Development of Healthy Eating Behaviours during Childhood

Alison K. Ventura

Department of Nutrition Sciences College of Nursing and Health Professions Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pa., USA

The Nest 2013

Preferences are a strong driver of children’s dietary intake. Young children show innate preferences for sweet, salty, and savoury tastes and aversion to bitter tastes, but also a strong propensity to learn from experience. Healthy eating behaviours can be promoted by repeatedly exposing children to healthy foods, pairing novel healthy foods with familiar, preferred foods, and introducing new foods in a positive social context. Preferences are a strong driver of children’s dietary intake.

Young children show innate preferences for sweet, salty, and savoury tastes and aversion to bitter tastes, but also a strong propensity to learn from experience. Healthy eating behaviours can be promoted by repeatedly exposing children to healthy foods, pairing novel healthy foods with familiar, preferred foods, and introducing new foods in a positive social context.

Preferences are a strong driver of children’s dietary intake [1]; thus, an understanding of the factors that influence food preferences is an essential basis for understanding how preferences can be moulded to promote healthful eating behaviours. The abilities that underlie food preferences and eating behaviours – taste, smell, and oral motor skills – develop long before an infant’s first direct experience with solid foods. The development of taste and smell systems begins in utero and both senses are functionally mature by the third trimester [2, 3]. Additionally, the foetus begins to swallow significant amounts of amniotic fluid by late gestation [4]. Prenatal functioning of these abilities prepares the foetus for later feeding behaviours and acceptance of the postnatal diet. Neonates exhibit both unlearned and learned behaviours that guide feeding and shape food acceptance patterns. Unlearned behaviours include preferences for sweet [5] and savoury tastes [6] as well as aversion to bitter tastes [5]. A preference for salty tastes emerges at 4 months of age [7]. Several innate reflexes that support feeding abilities, such as rooting and sucking, are also present at birth. Learned responses include preferences for stimuli experienced in utero, such as taste and odours from the mothers’ diet that are transmitted through the amniotic fluid [8].

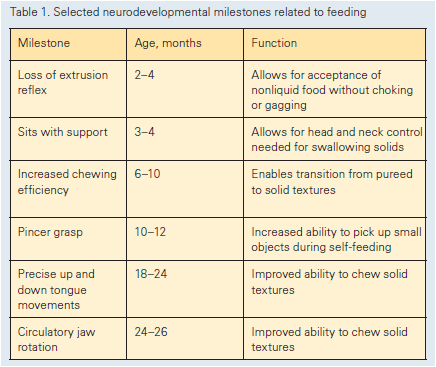

Taste and smell preferences, as well as neuromuscular skills necessary for solid food consumption, continue to develop postnatally. Tastes and odours from the mothers’ diet are also transmitted through the breastmilk, and infants learn to prefer these flavours [9]. Similarly, formula-fed infants show preference for the specific flavours of the formula they are given [10]. Table 1 outlines several cognitive and motor milestones that prepare the infant for the eventual transition from a milk- to a table food-based diet.

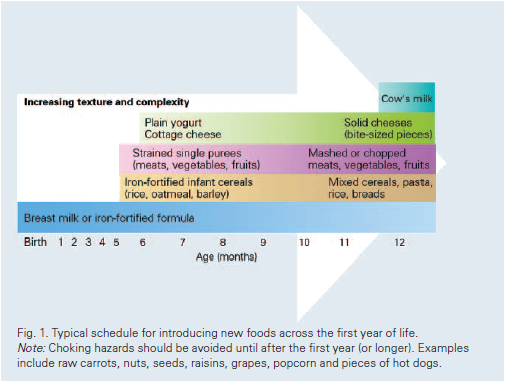

Figure 1 illustrates a typical schedule for introducing new foods. This transition can be difficult for caregivers attempting to instil healthy eating behaviours as young children (especially 2- to 5-year-olds) exhibit heightened levels of neophobia, defined as fear of new foods.

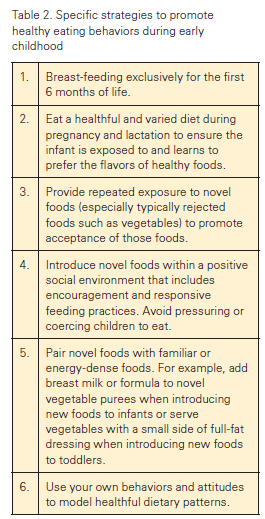

Additionally, the unlearned preferences mentioned above mean that young children will readily accept energy-dense and nutrient-sparse ‘kid’ foods, such as pizza and ice cream, and may reject healthier foods, such as green vegetables. Fortunately, young children also show considerable plasticity in preferences and can be guided toward healthier foods through repeated exposure [11], associative conditioning [12], and positive social contexts [13]. Table 2 outlines specific suggestions for how caregivers can use these strategies to promote healthy eating behaviours during early childhood.

References

1. Birch LL: Dimensions of preschool children’s food preferences. J Nutr Educ 1979; 11:77–80.

2. Bradley RM: Development of the taste bud and gustatory papillae in human fetuses;

in Bosma JF (ed): Oral Sensation and Perception. Springfield, Charles C Thomas, 1972, pp 137–162.

3. Schaeffer JP: The lateral wall of the cavum nasi in man, with especial reference to the

various developmental stages. J Morphol 1910; 21:613–707.

4. Pritchard JA: Deglutition by normal and anencephalic fetuses. Obstet Gynecol

1965; 25:289–297.

5. Ganchrow JR, Steiner JE, Daher M: Neonatal facial expressions in response to different

qualities and intensities of gustatory stimuli. Infant Behav Dev 1983; 6:473–484.

6. Steiner JE: What the human neonate can tell us about umami; in Kawamura Y, Kare MR

(eds): Umami: A Basic Taste. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1987, pp 97–123.

7. Beauchamp GK, Cowart BJ, Moran M: Developmental changes in salt acceptability

in human infants. Dev Psychobiol 1986; 19:17–25.

8. Schaal B, Marlier L, Soussignan R: Human foetuses learn odours from their pregnant

mother’s diet. Chem Senses 2000; 25:729–737.

9. Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK: Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by

human infants. Pediatrics 2001; 107:E88–E93.

10. Mennella JA, Forestell CA, Morgan LK, Beauchamp GK: Early milk feeding influences

taste acceptance and liking during infancy. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 90:780S–788S.

11. Birch LL, McPhee L, Shoba BC, Pirok E, Steinberg L: What kind of exposure reduces

children’s food neophobia? Looking vs. tasting. Appetite 1987; 9:171–178.

12. Anzman-Frasca S, Savage JS, Marini ME, Fisher JO, Birch LL: Repeated exposure

and associative conditioning promote preschool children’s liking of vegetables. Appetite 2012; 58:543–553.

13. Addessi E, Galloway AT, Visalberghi E, Birch LL: Specific social influences on the

acceptance of novel foods in 2-5-year-old children. Appetite 2005; 45:264–271.

If you liked this post you may also like